Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | Email | Google Podcasts | Stitcher | TuneIn | Spotify | RSS

INTRODUCTION:

Back in March 1973, Rayo and many of the most hardcore self-liberators of the time (and likely even today) published a massive 75,000+ word issue of VONULIFE, that is shockingly relevant and of immense value, even today.

And while that was a highlight, there was also an entire zine series of VONULIFE, which I recently digitized. As I finished up those last words of transcribing, it was with a heavy heart…until the idea hit me like a collapsing roof of a badly engineered underground shelter.

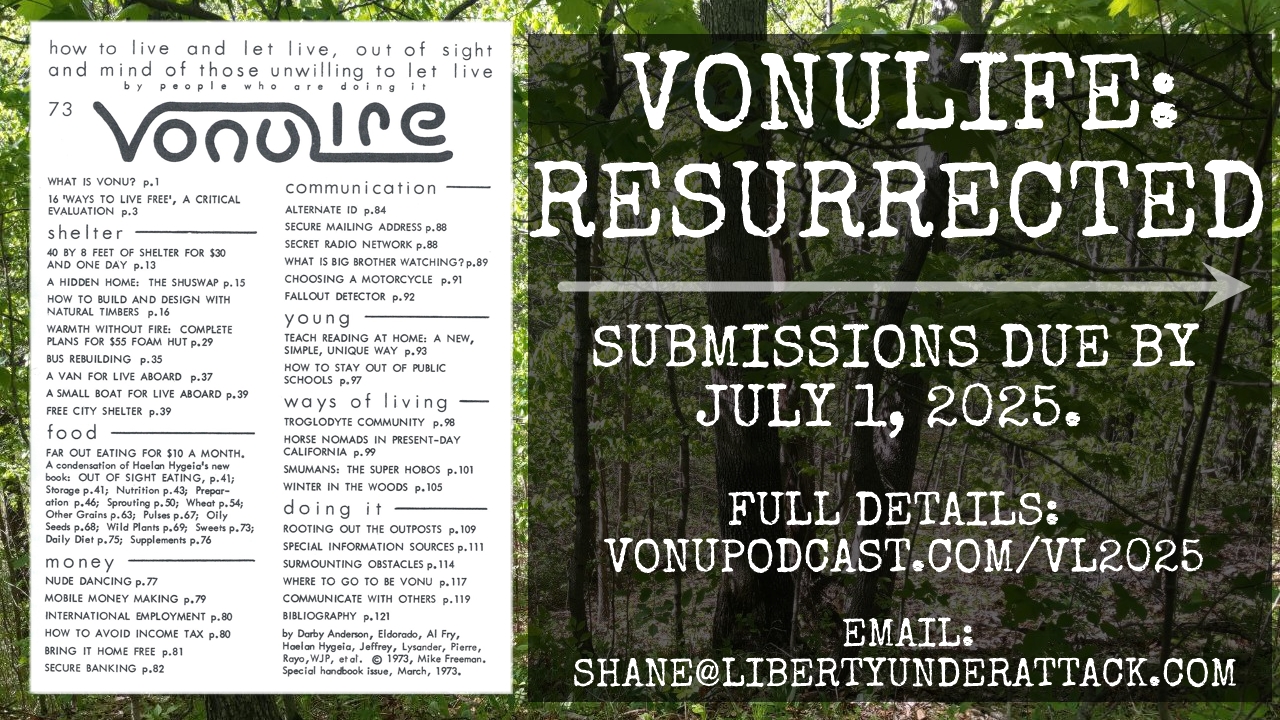

VONULIFE should most certainly be RESURRECTED, just as the overall freedom strategy of vonu has in the modern day and age. And if you know anything about VONULIFE, you know some of the GREATEST content came from contributors.

That’s where you come in – let’s dive into the plan.

THE PLAN

VonuLife, March 1973 was the only issue released in that year. Similarly, I think we should aim for one book a year, the first being VonuLife 2025. That will give ample time to acquire and create content, and to have plenty to report on as far as developments (or setbacks) of our liberated lifestyles.

Content

- Section 1: Situations & Searches

- Lifestyle reports from self-liberators: a report about your liberated lifestyle, things you’ve learned, your goals, what led you to vonuism/self-liberation, etc.

- Reviews of books, equipment, organizations, tips & tricks, etc. Information that you feel is valuable to pass on, that’s not in article form.

- Section 2: General Strategy

- Back in VonuLife’s heyday, topics sought out included: van nomadism, pedestrian nomadism, wilderness vonu, international travel, family & children, intentional communities, new country projects, financial independence, health liberation, vonu in cities, and underground shelters & troglydysm,

- We still want articles on ANY and ALL of those topics, but additional ones include: private communications, sovereign networking, vonuing in cities in the 2020s, alternative housing solutions (to combat cost), etc. If you’re curious about your topic in particular, just ask!

*Examples of both will be posted below.

Timeframes

- Any submissions must be made by July 1, 2025.

- After a few months of editing & preparing, we will aim for a Fall 2025 release.

Notes

- This IS NOT a general, “send us an article submission to fill space.” It has to be of the caliber that VONULIFE deserves and was founded upon: hardcore solutions/hardcore action, no political crusading & no collective-movementism; the principle of voluntaryism (that all interactions should be voluntary) must be maintained. I.e., don’t siphon (STEAL) gas to fund your van nomadism.

- General proofreading/editing will be done on every article, maintaining each author’s individual “voice”, but as always, editorial designs have to be made.

EMAIL SUBMISSIONS, QUESTIONS, IDEAS TO: [email protected]

~~~

SECTION 1 EXAMPLE:

EVOLUTION OF THIS LIBERTARIAN or HOW I GOT HERE FROM THERE BY ROBERTA (SEPTEMBER 1969)

Only a few months ago I was teaching in a state “gun run” school. It was my first and I had decided my last year of teaching in such a school. While at the job, I was thoroughly miserable and in search of a happier way of spending my life.

Since I felt that the U.S. Government was as bad as the Nazi regime had been, I was interested in a way of life whereby none of my earnings could be used to support a war machine. I had plans of going to Florida to work at a health resort in exchange for room and board as soon as my teaching contract expired (last June). That way, I hoped to avoid income tax and also learn about natural hygiene. (My weight was a terrible problem and I had great hopes of reducing at this resort.)

Before going on to explain how I got “here from there” I’ll fill in a little on how I got “there.” I’ll go all the way back to my grandfather.

As a young man, Grandpa fled from Russia to avoid being drafted into the Czar’s army. (Maybe he was running away from shulla too. Shulla wasn’t his girlfriend: it’s Jewish Sunday school, only on Saturday. Grandpa’s father was religious but Grandpa had other ideas, like he was an atheist.) Newly arrived in the U.S. and safe and sound from the nasty old Russian czar, Grandpa started to “work his way up in the world.” After years of hard work, he was owner of his own store (general merchandise). He also married. By this time, the U.S. Czar, commonly called Czar Samuel or translated “Uncle Sam” was after Grandpa. But a baby daughter exempted Grandpa from Sam’s army.

The baby was my mother. As a young girl, she was active in leftist, communistic political-action groups. (Today she is involved in groups like Women for Peace as opposed to communistic groups.) My parents were hounded by the FBI when I was little and I was taught to say “I don’t know” in case I were questioned. The police were DEFINITELY NOT our kind of people. When young, my mother took me to some picnic where Paul Robeson was to sing. The people living around the picnic rounds (Peekskill, N.Y.) didn’t like Negros or something and as we were being bussed home, I remember the local residents lining the streets with rocks – boulders – ready to throw. They threw them too. There was blood and broken glass and I can still see in my mind those people standing with their rocks and next to them were standing policemen: the policemen and the rock throwers were buddy-buddy.

So much for recollections of early childhood. While at my teaching job last fall, I received from my mother a copy of “Vocations for Social Change.” It’s a Bay Area publications which lists among other things, the School of Living. I wrote the School and subsequently subscribed to its newsletter THE GREEN REVOLUTION (Heathcote Center, Freeland, MD 21053, $4 per year), also receiving its book, GO AHEAD AND LIVE. But even though I agreed with many of their ideas, the prospect of homesteading left me with some reservations: like who would feed the chickens and milk the cows and water the crops when I was on a bicycling trip? In other words, I viewed being tied down to a homestead just like that; being tied down.

G-R was exposing me to libertarian ideas however. And it was in G-R that I saw an ad for PREFORM-INFORM which mentioned nomadic living. I suppose this appealed to me because I had dreams of getting on my bicycle and riding – destination, the world. I’d be a bicycle gypsy. One of the Preform editions came with a hand-printed note on it from this guy who said he was going to British Columbia and would it be O.K. if he were to stop by to see me on the way. I answered and said sure, stop by. And that’s how I met Tom, and found out who is John Galt and a few other things.

Tom came by on a Sunday. He stayed for the next few days. We exchanged literature. He gave me Rand’s ANTHEM to read. It made sense and with Tom’s help, I was able to dislodge some of the cobwebs of prejudice that had been woven in my mind by an upbringing in a leftist family atmosphere. Thus I was able to accept and adopt much of the philosophy of that small volume. After the days had become a week Tom asked me if I would like to go to B.C. with him. I thought about it (I can’t remember if twas for a minute or a day) and said “yes!”

So when school was over and all my stuff moved of the rented apartment I had been sharing with a friend, Tom and I were off to B.C. Tom drove the first stretch – I shelled walnuts and asked a lot of questions. Along the way north, we stopped to visit with other libertarians, exchange ideas, knowledge, ask and answer questions. It was all very stimulating. While in B.C. at our forest squat spot I read ATLAS SHRUGGED. I read it for breakfast, brunch, lunch, high tea, low tea, dinner, supper, and even by candle light. I loved every minute of it. It is a work of art, a work of genius, a phenomena in itself. Though I cannot meet the people in the book, I look forward to meeting and spending time with other libertarians as I would look forward to meeting John Galt, Dagny, and their friends.

Whereas before (when I was “there”) I was not opposed to government spending my money for “good” things, now (that I am “here”) I oppose government spending ANY of my money. I wish to be free to do as I see fit. Before I was concerned with helping to make this a better world for everyone. I am no longer concerned with everyone. Each must decide for himself what “better” is and then seek for that himself. What I now consider “better” is FREER and I will strive to be as free as I can and help those who feel the same way I do towards that end also, thereby increasing my own freedom.

I think my present goal – freedom for myself and those close to me here and now – is much more realistic than “trying to make this a better world.” (Of course by making my own world better I am indeed making the whole world better, but better only by my standards which I don’t ask everyone to accept.) Whereas before I was much in favor of ending the Vietnam War (or any and all war and arms races for that matter) what could I do? Write letters to my congressman? I never saw a piece of paper stop a bullet. But now I know just what to do. I can make damn sure that none (or an insignificant amount) of my money (energy) goes towards buying bullets and bombs and other things that are used to make wars. People ar still dying but I have no hand in killing them and I will be responsible only for my own actions. I will no longer allow anyone to use guilt as a weapon on me. There are people starving and people dying, yes. Before I felt I should join a cause to help these people: more letters to congressmen. Now I fell all I SHOULD do is my own part, e.g. not overpopulate the world or initiate force. I will not allow myself to be held accountable for other than my own doings.

Right now, Tom and I are at a squat spot overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Since we are opposed to the State, its bureaucracy and all its trappings, we feel it is not in our best interest to have a State marriage license. However, Tom has drawn up our own free-marriage contract. Each of us is a “freemate.” Also in the contract, Preform is a joint venture. Therefore, in the future, you’ll be hearing more from this “freemate.” –ROBERTA

~~~

SECTION 2 EXAMPLE:

SMUMANS: THE SUPER HOBOS By: Rayo

‘Smum’ stands for Seclusion and Mobility Using Multiplicity. Smum has some features of and intergrades with troglodyte, foot-nomad, urban anonymity, and vehicle-nomads ways, but is [it] differs in overall living pattern and equipment use. Smum has similarities to traditional ways as diverse as hobos, eskimos, fur trappers with several overnight cabins, and wealthy families with several ‘conventional’ houses.

Many smum life-styles are possible but all involve migration among various abodes. The abodes are usually simple, inexpensive, semi-permanent and widely separated. A number of towns of a region are used, in succession, as trading outposts. Smum offers, in part the wide-ranging mobility and anonymity of vehicle nomadism with the privacy and safety of troglodysm. While smum is complicated to describe (at least with conventional concepts), smum is easier to implement than any other life-style I presently know of which offers comparable vonu. Smum is made economical by the low cost of plastic film and second-hand utensils.

A smum family migrates between its abodes, probably seasonally. Less often an abode is moved to a new site within the same area, or phased out in favor of a new abode developed elsewhere.

Most of the abodes are located at least a quarter-mile and not more than ten miles from a road. The road is preferably either a highway, or a trail without habitation along it or at its intersection with the highway. Most abodes cannot be reached by motor vehicles. There are several hiking routes from each abode to one or more such roads. Each route reaches the road at a different place and at a place out of sight of residences. At least one route from each abode ends in a parking spot which is out of sight of the road and rarely used – suitable for unloading supplies.

A few hundred yards into the brush from each parking spot is a stash for low-value supplies awaiting backpacking to the abode. The supplies are stored in drums for protection from animals and weather.

Hiking routes are irregular and cannot be followed by someone not familiar with them. Each route is used only a few times a year so it doesn’t receive much wear.

In Siskiyou region, abode sites are selected so that highway distance between is typically 100 miles. This separation is determined be the distance between major trade towns and the living patterns of conventional people – people rarely go a hundred miles to work, shop or socialize. Overland hiking distance between abodes is less – typically 30 to 40 miles – the abodes all lying within the same mountain range.

A family has no single trading outpost. From each abode a different town or, better yet, two or three in alternation are used for shopping, receiving forwarded mail, and perhaps temporary employment. The towns so used are fairly large – at least 5,000 people within shopping range. And they are located on major highways and thus accustomed to many visitors.

After living at one abode a few months and making trips alternately to the nearest suitable towns (which preferably lie in opposite directions) the family moves to another abode, a hundred miles away, and makes trips to different towns. And so forth. They do not return to the first abode and the corresponding trading outposts until a year has passed. If a family has six abodes, 12 trading towns, and makes trips to town twice a month, one member is in each town twice a year, not often enough to be distinguishable from the many thousand travelers who stop briefly.

The family is probably not limited to a fixed schedule or route. If they encounter trouble in one town they do not return to that area for several years, meanwhile developing a new abode elsewhere. In an emergency they can hike overland between abodes without using roads or going into populated areas.

All possessions of a smum family have one or more of the following characteristics: inexpensive, expendable, small, used seasonally. Inexpensive items are duplicated and left at each abode. These might include polyethylene film and rope for rigging tents, bedding, cooking stove, utensils, extra clothes, and drums for storage while abode is not occupied. Bedding, clothes and utensils are scavenged at dumps or purchased second hand. Total cost of stationary items at a warm-weather abode is probably less than $50. Expendable supplies include food staples, soap, writing paper, kerosene and propane. These are ordinarily left at an abode until consumed. Some small but valuable items move with the family; such things as watch, transistor radio, binoculars, handgun, radiation detector, camera, medical kit, sewing kit, and often-used reference books. Seasonal items are grouped according to use at specific abodes; these include most books, tools and construction materials.

Each abode is somewhat specialized for the activities performed there and the season that it is used. Abode might include: Summer camp: This may be more remote than other abodes since there will usually not be snow and swollen rivers to hinder access. If foraging and vonu horticulture are accomplished in that area, books, tools, and preservation equipment are stored there. A plastic tent and mosquito netting are sufficient shelter.

Winter abode: This may be a semi-underground structure, or a large foam hut plus a plastic tent. Since there is little warm working space much reading and writing are done there. Most books are stored there.

Electric abode: A small generator, probably hydroelectric, powers a sewing machine, electronic equipment, or any other gear requiring electricity but not bulky imports. Relevant books and materials are stored there.

‘Edge place’: This is for work involving bulky imported materials such as carpentry, and is the one abode accessible to vehicles. Major work on any vehicles is performed there; also any work which because of space required, noise or smells is not easily vonued. Edge place is most likely on fairly secluded private land leased from a friendly landowner. An old van or house trailer may be parked there to provide sheltered work and storage space. Edge place is much less vonu than other abodes so work requiring much privacy is not performed there. And any family members especially threatened, such as slave-age children during that season, remain elsewhere.

A minimally-furnished van may be used for shelter if one or more members occasionally go into that society to earn money. When not in use it is probably parked on private land, perhaps at edge place.

A friend who may be outside the Siskiyou region provides a permanent mailing address. The friend accumulates mail, bundles it, and sends it as a parcel, as directed. If possible the family makes arrangements with trustworthy local people in each town to receive U.P. parcels; if not the parcels come general delivery.

A legal home address for driver’s license and vehicle registration, if needed, is probably arranged in a large city outside the region, and separate from the mailing address.

Means of transportation vary. One smuman may not have any vehicle. E hitchhikes for mail and light supplies, also for migration between abodes. E hires a van or pickup, preferably a transient, to haul heavier supplies.

Another smuman may use a motorcycle for all transport – this will be a bike with enough power for the highway yet light enough to manhandle into hiding places – perhaps a 250cc trail bike.

Still another may have a van or camper for hauling supplies as well as for work excursions. E will also use a motorbike or else hitch rides, since places suitable for long-time parking will seldom be convenient to unloading spots.

Smumans, like other vonuans, obtain money in ways which minimize time and involvement with the Servile Society. One may have a line of special services or products e sells thru merchants in the towns e visits. Another may have a mail-order enterprise. Someone with a highly-paid skill may journey to a distant city for temporary employment.

But most, at least at first, will probably depend on day labor in nearby towns and seasonal crop work. Although this is low paying, a smuman’s expenses can be very low. So not many day’s work are needed.

An individual or family without slave-age children can be flexible about outside employment – working together or separately at any time of the year. A family with children is more constrained. Perhaps during the school year the children remain at a secluded site, then during Summer the whole family does crop work and any other activities involving that society.

If asked for address by employers or bludg, a smuman gives er legal home address. If asked for local address e says e is visited by some friends (location vaguely defined).

A smuman can be opener with outsiders than can be a more-stationary wilderness-vonuan. In some instances e may be able to socialize with local non-vonuans. E can even say to friends e is camping ‘back in the woods’, knowing e will have moved on to other woods before the word gets very far.

For a smuman, the whole Siskiyou region becomes, in a sense, a single widely-dispersed city of several hundred thousand people. Smum offers much of the anonymity of metropolis without the pollution or nuclear danger. Assets are dispersed and cannot be destroyed by a single misfortune.

Comparing smum to full-time van living: Most time is spent in or around abodes which are concealed away from roads in rugged, brushy areas rarely if ever penetrated. With our van the greatest mean time to harassment (mth) we have achieved is one or two years. Whereas with a small tent we can easily achieve 20 years mth; with more work and care, 200 years mth. (Interpretation: if there are 200 such camps, an average of one a year will be discovered.) This is while a camp is set up; torn down and stuffed in drums under bushes chance of discovery is even lower. We have had enough stash tents in enough situations to have confidence in the 20 year figure. One year mth is adequate for someone not especially threatened who wants peace and quiet. It is not sufficient for slave-age children, someone without ‘acceptable’ ID, or for most kinds of alternate-economy enterprises.

A serious disadvantage of smum for some: activities must be accomplished at certain places and in certain seasons, rather than when one is in the mood. Planning and bookkeeping are essential. Life is more structured than with everything in one place, but the structure is chosen by oneself, not imposed by outsiders.

One might initiate a smum life-style by exploring a region on foot and hitchhiking, using light-weight camping gear, then gradually build equipment and supplies at the most desirable spots. Or a van nomad might develop a string of vehicle squat-spots; then use these as bases for scouting. On the other hand, from a smum life-style one can become, say, a troglodyte by further developing one abode and phasing out the others.

Like any new life-style, smum should be begun when one is not in immediate danger — when one has time to experiment and can survive a few mistakes.